Page 22

— Office Properties Quarterly — January 2015

Design

“S

leeping giants” are not

fairy tale creatures or his-

toric architectural icons

like the Empire State

building in New York City

or the Wells Fargo Building in Denver.

Sleeping giants in corporate real estate

are the vast stock of older, more pro-

saic buildings domi-

nating our skylines.

Sleeping giants are

valuable building

assets that struggle

to compete as cities

change around them

and new buildings

enter their markets,

luring away prime

tenants.

What these build-

ings have in com-

mon, given their

age, is that they

were built before

a large number of

form-giving developments in building

technology were introduced. Before, for

example: Ethernet was standardized in

1983; cellular telephones were intro-

duced in 1984; the Internet backbone

was created in 1992; the U.S. Green

Building Council was established and

underfloor air systems were incorpo-

rated into signature projects in 1993;

and building automation systems

emerged around 2000.

These buildings were planned and

designed for a traditional idea of the

corporate office environment, well

before Richard Florida chronicled the

rise of the creative class of workers in

2002 and pop culture lambasted the

drudgery of high-walled cubicle envi-

ronments in movies like “Office Space”

and “The Incredibles,” not to mention

the ubiquitous Dilbert comic strip from

the mid-1990s.

These buildings have very little of the

amenity infrastructure to help them

compete with the redefined workspace

led by creative 21st century firms like

Google, which went public in 2004.

That same year, Google’s free-spirited

approach to workspace was widely

published and won numerous design

awards.

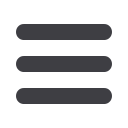

To illustrate the scale of aging asset

inventory across the country, we ana-

lyzed building data across 14 key U.S.

corporate real estate markets. We built

our analysis from JLL’s Spring 2014 US

Skyline Review. The buildings repre-

sent the top-quality urbanized office

micromarkets in each city. We graphed

today’s buildings by year completed

since 1950 to show that the vast

majority of our current multitenant

office buildings were in place by 1990,

which was 25 years ago. This building

landscape is familiar to us, we can see

it down many streets in Denver, and

this is the opportunity to reposition

assets facing our industry.

While new office tower construc-

tion is exciting, the bigger and more

enduring story lies in understanding

how the buildings in the background

must reposition themselves to remain

relevant. The bottom line is that aging

assets become candidates for repo-

sitioning when there is evidence that

investment will result in higher occu-

pancy, increased rental rates and a

positive return on the investment.

Asset Considerations

Key considerations for asset own-

ers contemplating repositioning their

aged assets are the current and desired

market position of the space, timing,

potential revenue and approach.

Market position in corporate real

estate is often described by class. In

Denver, there is a large inventory of

Class A buildings, with a small subset

identified as Class AA. When an owner

believes an asset has potential to per-

form like a Class A or AA property, but

knows that the asset is widely con-

sidered a Class B building by the local

market, improving that market percep-

tion of the building can be a primary

driver of a repositioning investment.

Timing is a crucial factor. First,

consider the duration the property

will be held and resulting window

for improved returns to materialize.

Some repositioning investments will

impact revenues more quickly than

others. Second, when new buildings

are coming on line that may compete

for desirable tenants, strategic repo-

sitioning projects can take advantage

of relatively short delivery cycles and

beat a ground-up construction project

to market. Finally, a major vacancy

can trigger repositioning, offering both

incentive to improve leaseability and

simplified construction.

Revenue concerns often trigger

repositioning. To justify the invest-

ment, asset owners must believe that

material increases in rental rates can

be achieved and the building will be

leased more quickly. Alternatively,

doing nothing may risk a reduction in

rental rates over time, and increased

difficulty leasing up vacant space. Yet

revenue forecasting models are limited.

Predicted return on any investment is

based upon best-guess assumptions

and may change as unanticipated fac-

tors impact market conditions.

Key to effective repositioning is to

take a fresh look at the property. Asset

insiders may find it difficult to imag-

ine all the viable possibilities. A design

competition can be a great tool to

solicit ideas before finalizing the proj-

ect scope and selecting a design team.

Offering payment helps to ensure that

design firms will dedicate their best

resources, and setting up the competi-

tion brief with minimal guidance from

the owner can free designers to gener-

ate unexpected visions for the project.

Releasing Value

Through experience across numer-

ous repositioning projects, we have

identified 10 key approaches to pin-

point and unlock trapped asset value.

1. Ask local experts –

People most

familiar with the building are a great

resource for ideas and possibilities.

Beyond the owners, leasing agents,

property managers and facilities team,

we find it beneficial to reach out to

people in the market such as brokers

and tenants who interact with the

property from the outside and offer a

broader view of prospective tenant per-

ception and market demand.

2. Quantify anecdotal trends –

Follow

up on informal conversations by quan-

tifying relevant trends in your market.

One approach is to compare develop-

ment activity on a timeline to highlight

relationships and illustrate dynamics

unique to your market. Tracking the

changes in downtown Denver over

time highlights the role of residential

development. Hotel room availability

has grown dramatically over the last

decade, but the number of residential

units downtown has been growing

steadily since the early 1990s. While

almost half the inventory of multiten-

ant office space in Denver was built by

1985, unlike many cities that are only

now seeing growth from that base,

the Denver market has steadily added

office properties since 2005.

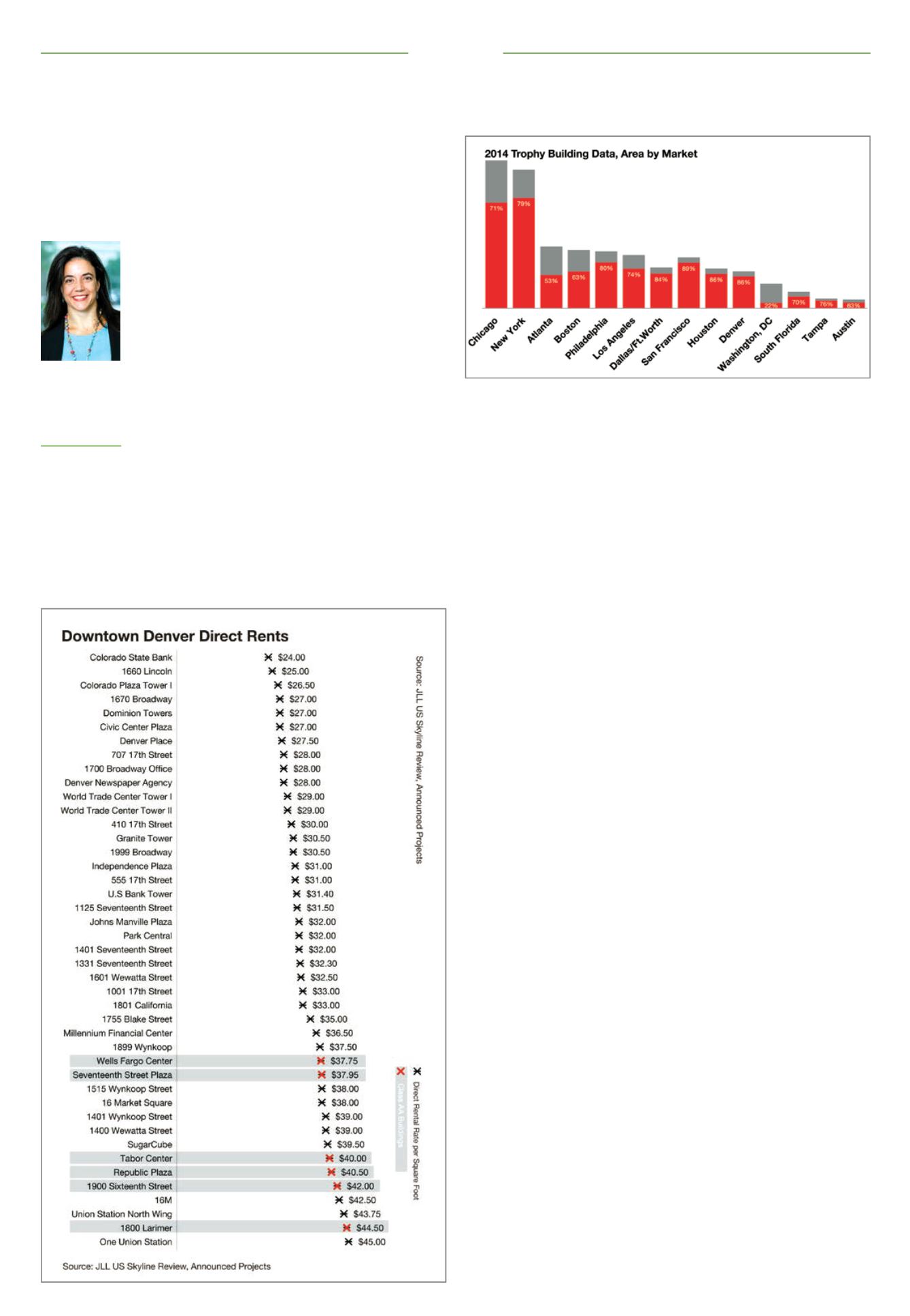

3. Investigate market dynamics –

Com-

petitive data is available from numer-

ous sources and can be used to under-

stand what the key competitive drivers

are in a particular market and identify

assets that may be poised for reposi-

tioning. Plotting the trophy buildings in

downtown Denver on a graph sorted by

direct rents shows a fairly large spread

in Class A rents across the market

(from about $24-$45 per sf). Surpris-

ingly, the properties identified as Class

AA do not command the highest rents

in the market.

This observation invites a closer look

at market competitiveness. A quick

re-sort to separate the buildings by

location within downtown adds clarity.

Grouped first by location, then sorted

by rent, the Class AA buildings rise to

the top in the core commercial area

group. While buildings are much larger

and the scale of building inventory

is far greater in the core commercial

area, the average direct rent for the

Lower Downtown/Central Platte Valley

buildings (about $38) is greater than

Sleeping giants and aging assets are everywhereJamie Flatt

Associate

principal, Page.

Page has offices

throughout the

country, including

Denver.

Seventy percent or more of the 2014 trophy-building stock in 10 of the 14 markets

was in place by 1989.

Existing Class A multitenant buildings, sorted from least to greatest rents