Page 12

— Multifamily Properties Quarterly — January 2015

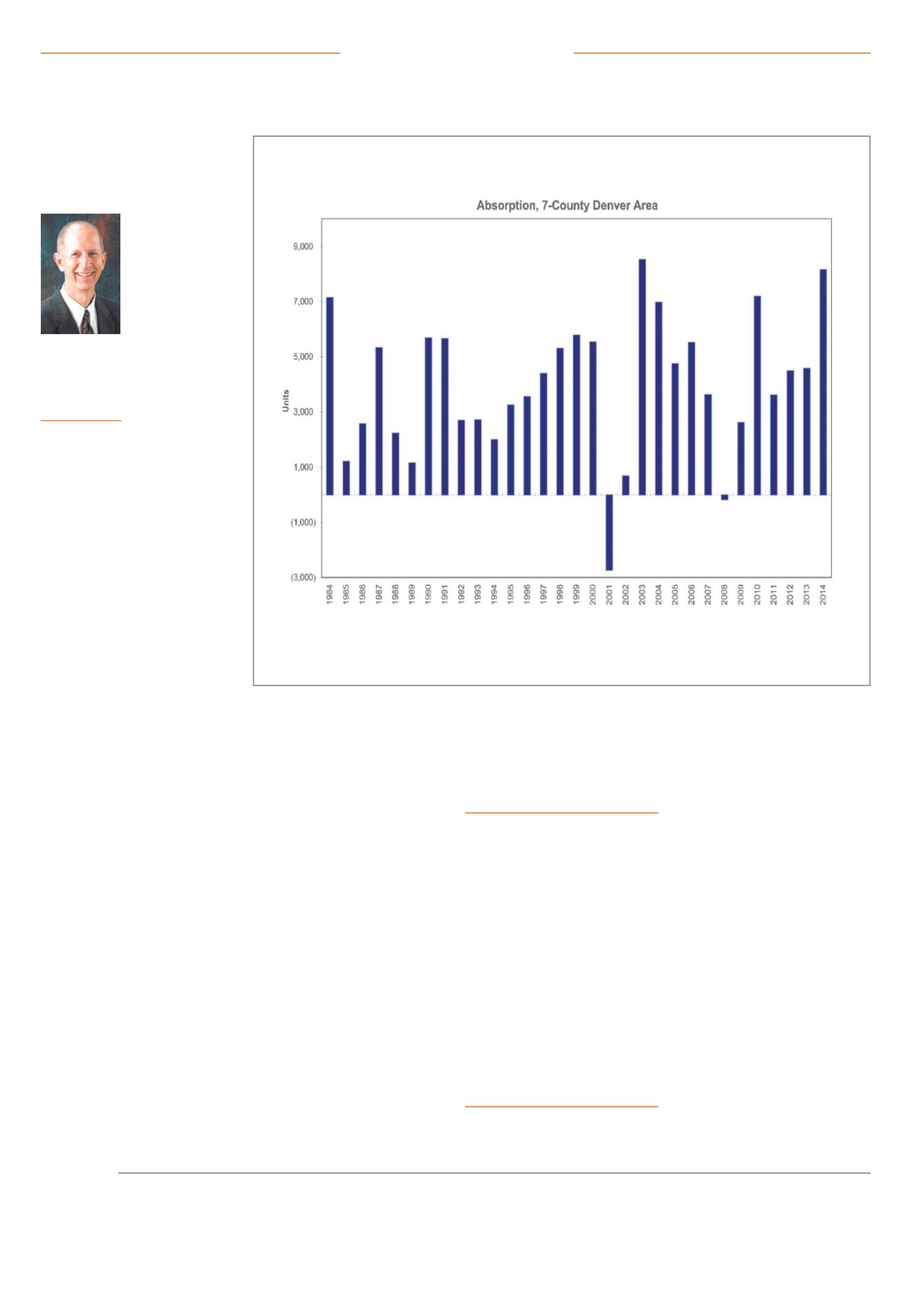

A

prominent question fac-

ing the apartment industry

is, “Can we absorb all of

the new apartments being

built?” Followed by, “If not,

then what will happen?” Looking

back, we can see

that absorption

varies tremen-

dously from year

to year, so any

forecast is likely

to be slightly to

highly inaccurate.

The accompany-

ing chart shows

just how variable

apartment absorp-

tion has been in

the Denver metro

area over the past

30 years, from neg-

ative 2,700 units

in 2001 to positive

8,500 units only two years later, an

11,200-unit swing.

There is often a correlation

between increasing absorption and

increasing new supply. This makes

sense from a couple of perspectives.

First, apartments typically are con-

structed when the local economy

is doing well, jobs are being created

and population growth is accelerat-

ing from in-migration. So, absorp-

tion should be higher when apart-

ments are being built, if they are

built at the right time. Absorption

is also higher when a large sup-

ply of new apartments is added,

because new apartment buildings,

unlike office buildings, for instance,

do not sit empty in the absence of

adequate new demand. Rents get

reduced, initially in the form of

increasing concessions, until the

desired absorption rate and final

occupancy level are achieved. If

there is inadequate demand, resi-

dents look for new properties and

are pulled away from older proper-

ties, resulting in overall vacancy

increases across the market.

Older properties then react by

offering concessions or reduc-

ing rents to achieve their desired

occupancy. The resulting lower rent

levels make apartments afford-

able to more people, expanding

demand. This expansion occurs

because roommates can now afford

their own apartment, and more

adult children living at home can

afford to rent an apartment. In this

respect, supply can create its own

demand. But if new supply is exces-

sive, vacancy also will increase and

rent growth will decline, eventually

turning negative if vacancy gets

high enough.

Note in the chart that there was

very strong absorption during 2003

and 2004, a period of high vacancy,

but very low levels of new con-

struction. Similarly, 2010 achieved

strong absorption with no obvious

reason (the economy was weak at

the time), other than possibly the

fear from the financial meltdown in

2008 had subsided, the only other

year with negative absorption. Rent-

ers seemed to emerge from their

parents’ basements and ventured

out to rent a place of their own,

often with their parents’ financial

support.

Looking back, absorption has

averaged slightly more than 4,000

units per year over the last 30-plus

years, and just over 5,000 units per

year going back 50 years. But it has

almost always been either higher

or lower in any given year – rarely

at the average level. Current con-

ditions support higher rates of

absorption, supported by above-

average job growth, strong popula-

tion growth – particularly in the

typical renter age group – a limited

supply of new affordable housing

(think condos and townhouses) for

sale and limited financial means for

large segments of the population

(flat incomes, high student debt,

lack of a down payment, a need to

be mobile for the job market). Given

these positive factors, my original

absorption forecast for 2014 was

6,000 units, 50 percent above the

30-year average. This turned out to

be low, as slightly more than 7,000

units were absorbed in conventional

rental communities with 50-plus

units (from an inventory of 177,000

rentals), and just over 8,000 units

were absorbed, including both con-

ventional and affordable properties

(taken from the Apartment Insights

survey of over 200,000 units each

quarter).

While 2014 was an extraordinarily

strong year for absorption, it seems

likely that a similar number could

be achieved again in 2015, as little

on the demand side has changed. It

appears that even more apartments

are likely to be built this year than

last. Rents now are at even higher

levels, and the volume of new for-

sale housing is steadily increasing,

which could arguably slow absorp-

tion in the coming year. Either way,

2015 absorption is likely to be below

the 9,200 new apartments added to

the rental pool during 2014, and the

11,000 units expected to be com-

pleted during 2015. This assumes

there is enough available labor to

complete them. This gap between

supply and demand should push

vacancy rates higher, particularly

in submarkets with heavy con-

centrations of new construction.

The expected result is slowing rent

growth. Since metrowide rents grew

by an astounding 12 percent last

year, there is plenty of room for

rent growth to decline and yet still

be positive.

s

The outlook for absorption rates andwhat it meansApartment Insider

Cary Bruteig,

MAI

Principal,

Apartment

Appraisers &

Consultants,

Denver

Source Apartment Appraisers & Consultants, Inc.

Apartment absorption rate over the last two decades

of opportunities in the marketplace.

The majority of the $200 million

trading hands in the second half of

the year came through two portfolio

sales. One comprised McWhinney’s

sale of three properties (two in

Loveland and one in Westminster)

and the other was made up of three

student-housing properties sold in

Fort Collins by Walnut & Main.

Overall, 2014 was a fantastic

year for the multifamily market in

Northern Colorado. Owners and

managers were able to fill their

properties with eager tenants.

Rents continued their climb while

vacancies continued to be minimal.

Sellers were able to maximize the

values in their properties through

extremely low cap rates and never

before seen demand.

With rental rate increases far

exceeding inflation, 2015’s activity

will be watched cautiously with the

anticipation of pricing and vacancy

leveling off. With inflation meekly

increasing somewhere between 1.6

percent and 2 percent, combined

with very high housing prices, I

expect to see continued excellent

performance on the operational

side of the multifamily market

along with stabilized rents and

moderate vacancy.

s

Northern Continued from Page 7If new supply

is excessive,

vacancy also will

increase and rent

growth will decline,

eventually turning

negative if vacancy

gets high enough.