10

Gulf Pine Catholic

•

July 18, 2014

Gulf Pine Catholic

•

July 18, 2014

11

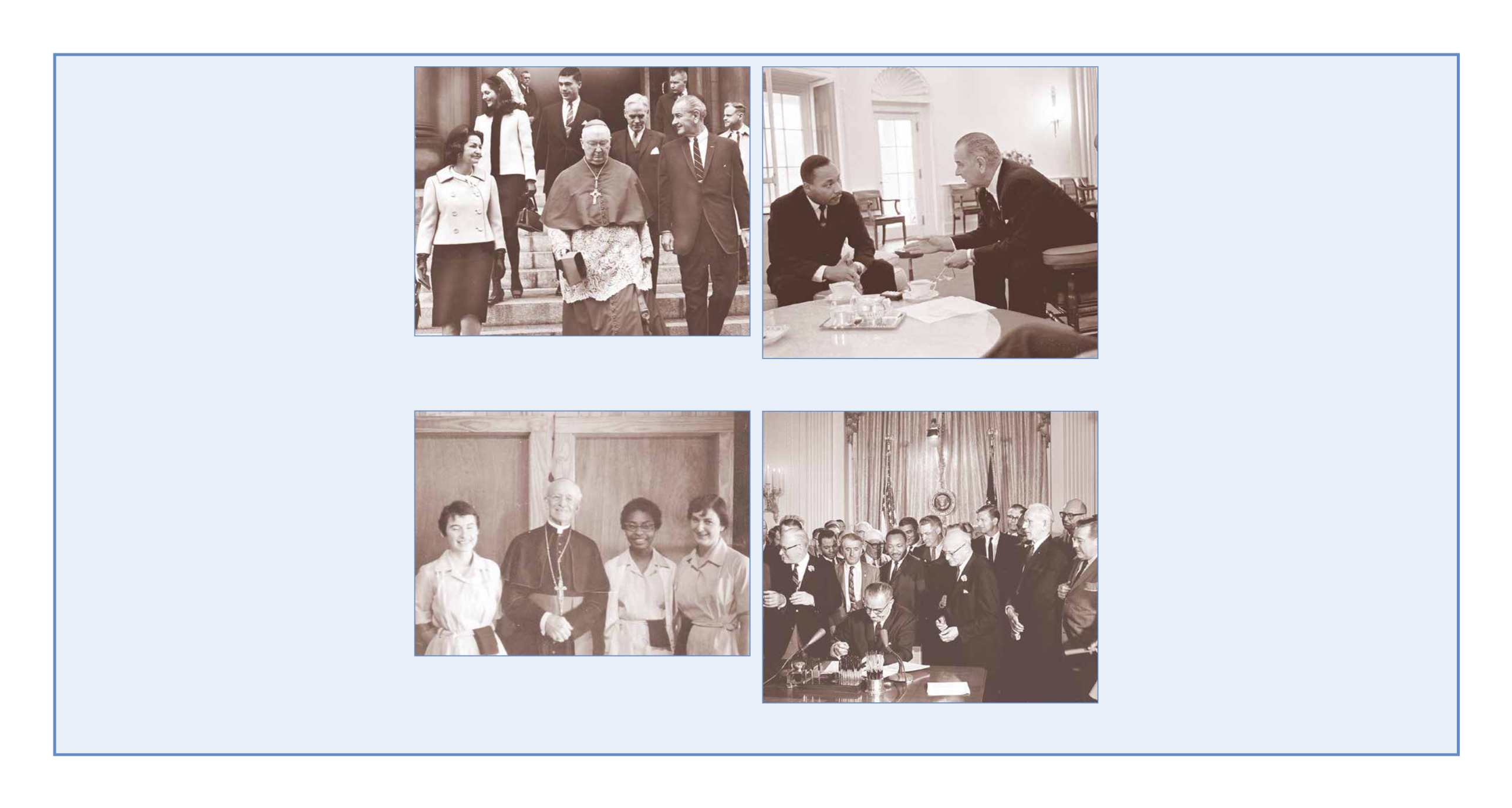

Then-Archbishop PatrickA. O’Boyle ofWashington walks with U.S. President

Lyndon B. Johnson following a 1968 Mass in Washington. The archbishop,

who was later named a cardinal, was a vocal supporter of the Civil Rights Act,

signed into law by Johnson July 2, 1964. He also integrated Catholic schools in

the Washington Archdiocese 16 years before the Civil Rights Act.

CNS file photo

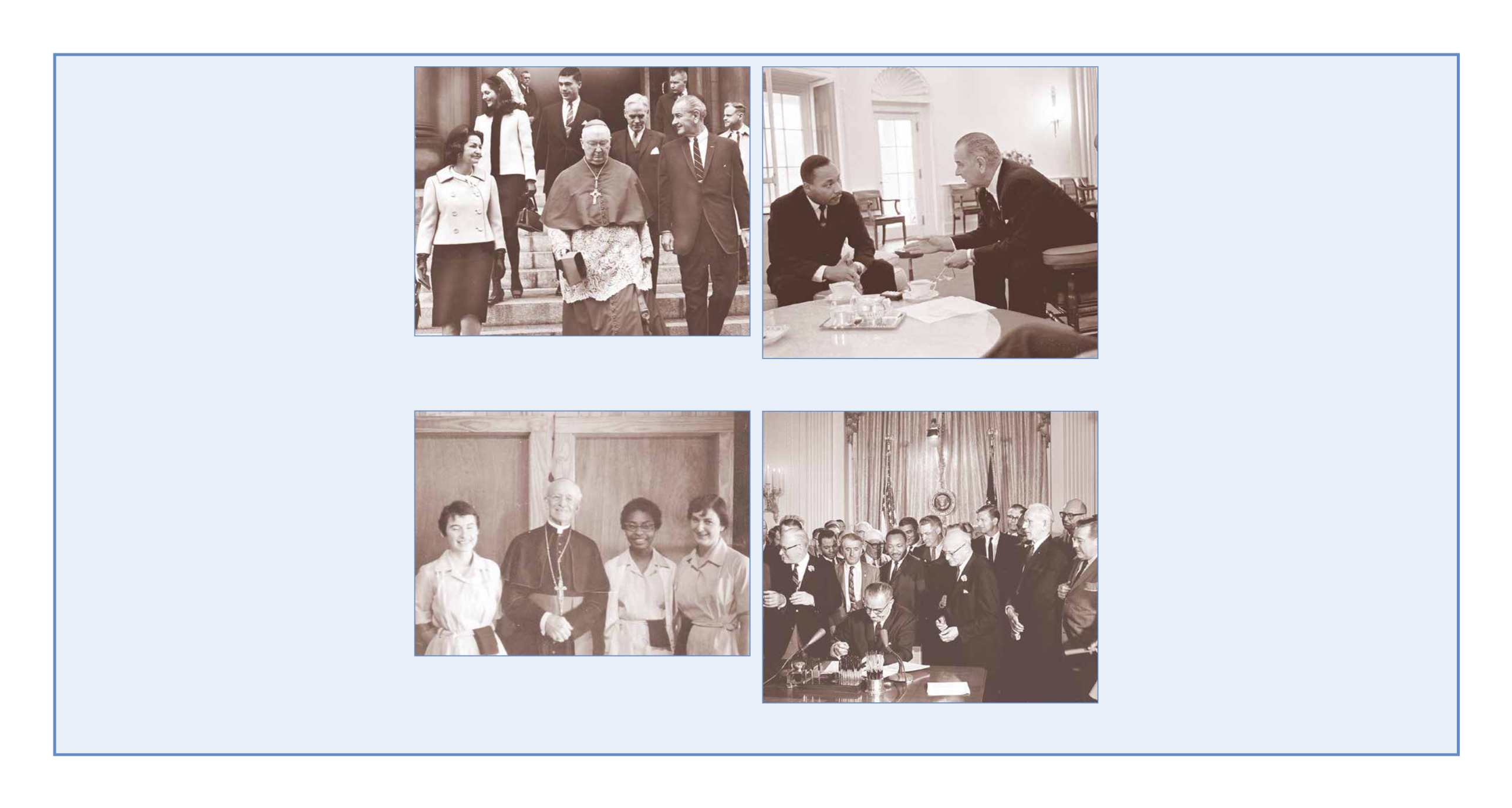

Civil rights leader the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. talks with U.S. President

Lyndon B. Johnson. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into law July 2, 1964.

CNS photo/Yoichi Okamoto, courtesy LBJ Library

Mississippi Bishop Oliver Gerow is pictured in this 1960 photo with members

of Pax Christi in Greenwood, Miss. Bishop Gerow, head of the Diocese of

Jackson, Miss., from 1924 to 1967, steered Catholics in the state through some

of the darkest days of the civil rights movement. He released a statement

urging lawmakers to support the Civil Rights Act of 1964, signed into law by

President Lyndon B. Johnson July 2 of that year.

CNS photo/courtesy Diocese of

Jackson Archives

U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act into law July 2,

1964, as the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and others look on.

CNS photo/Cecil

Stoughton, courtesy LBJ Library

Reflections on Civil

Rights Act: Progress

made, work still to do

By Carol Zimmermann

Catholic News Service

WASHINGTON (CNS) -- Fifty years ago, when the Civil Rights Act was

signed into law July 2 by President Lyndon Johnson, two Louisiana-born men did

not feel the earth move, but they knew it was the beginning of a time of change.

Norman Francis, president for student affairs at Xavier University in New Or-

leans at the time, described the law’s passage as part of a “watershed year.”

After living for more than three decades “under Plessy” as he says, referring to

the Supreme Court decision upholding racial segregation and “separate but equal”

facilities, Francis said it was hard to imagine that he had graduated from law school

but still “couldn’t walk into the front door of a restaurant until 1964” when the

civil rights law prohibited racial segregation in schools, workplaces and public

facilities.

But even graduating from law school was no small matter. Francis was the first

African-American to be admitted to law school at Loyola University New Orleans

in 1952 and he is just reading now about the efforts by local priests that went into

getting him admitted.

Now, his name is almost synonymous with Xavier University, the country’s

only historically black Catholic university, where he attended as an undergraduate

and held various positions until being named president in 1968, a role he was asked

to assume on the day of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination.

In an interview with

Catholic News Service

on the university’s campus June 12,

the longtime president, who is 83, showed no interest in retiring. He was quick to

praise the school, founded by St. Katharine Drexel and her Sisters of the Blessed

Sacrament, not only for its educational accomplishments but also for quickly get-

ting itself out from under 6 feet of floodwater from the breached levees following

Hurricane Katrina.

Francis, born in Lafayette, Louisiana, along with his four siblings, said the

separate-but-equal segregation “was a monster of many proportions on the human

spirit.” He also said his parents, who never graduated from high school, “had to be

the greatest psychologists in the world to have us keep our bearings while going

through this.”

They always stressed the importance of education and faith, he said, and it

seems the Francis children took this message to heart.

“We never lost our faith; our faith brought us through all of it,” he said of he

and his siblings including his brother Joseph, a priest with the Society of the Divine

Word who became one of the nation’s first black Catholic bishops.

The college president said his brother was active in the civil rights movement

along with a number of priests and nuns who took part in protests and marches and

were a “credit for the church.”

Auxiliary Bishop Joseph A. Francis of Newark, New Jersey, who died in 1997,

chaired the committee that wrote the 1979 U.S. bishops’ pastoral letter on racism,

“Brothers and Sisters to Us,”

which called racism a sin.

The bishop gave talks around the country years after the pastoral letter was is-

sued challenging Catholics not to just talk about eradicating racism but to do more

about it.

See WASHINGTON LETTER, page 15

U.S. bishops backed

Civil Rights Act, urged

people to make it work

By Carol Zimmermann

Catholic News Service

WASHINGTON (CNS) -- Catholic leaders supported the Civil Rights Act of

1964 and also urged Catholics to get behind the law to make it work, according to

the yellowed pages of typewritten articles in the

Catholic News Service

’s archive

folders.

The articles, written by

National Catholic Welfare Conference News Service

,

a predecessor of

CNS

, are headlined in all capital letters:

“Churchmen hail rights

law, urge cooperation”

and

“Churches had big part in rights bill passage.”

The reaction piece of July 3, 1964, the day after the legislation was signed into

law by President Lyndon Johnson -- and additions to the story in subsequent days

-- quotes several Catholic bishops and lay leaders rallying behind the legislation

that prohibited racial segregation in schools, workplaces and public facilities.

Los Angeles Cardinal James F. McIntyre called the law a “concrete expression

of the conscience of all men of good will” that has been the “concern and work for

the church for many long years.” And Washington Archbishop Patrick A. O’Boyle,

who integrated Catholic schools in the Washington Archdiocese 16 years before

the Civil Rights Act, described the legislation as a “tremendous national step for-

ward.”

Putting the law back in the hands of American citizens, Atlanta Archbishop

Paul J. Hallinan warned that if the civil rights law was “evaded or flaunted, both

sides will lose and Georgia and the American nation will suffer.”

Similarly, Msgr. George Higgins, director of the social action department of

the National Catholic Welfare Conference, a predecessor to the U.S. Conference

of Catholic Bishops, said the act will be “of little avail unless the great mass of

American people are prepared to go beyond the letter of the law and to help create

an atmosphere of mutual understanding and racial brotherhood in their neighbor-

hoods and communities.”

And in a joint statement issued July 3, 1964, the bishops of Louisiana urged

Catholics not just to obey the letter of the law but to “heed the voice of their con-

science in observing its spirit.” They also stressed the need to “put aside hatred,

agitation, repression and any other extremes.”

Similarly, Bishop William G. Connare of Greensburg, Pennsylvania, urged a

group of Catholic laymen to be “in the vanguard” of those making sure the law

was obeyed.

Frank Heller, president of the National Council of Catholic Men, certainly did

not need prompting about this. He said the new law put the nation “on the verge

of a ‘release from racism.’” But he also warned Americans not to let the new law

“atrophy into a meaningless gesture.”

“Future generations will live in shame if this becomes for history merely ‘one

brief shining moment’ when this nation gave witness to the dignity of all her citi-

zens,” he said.

An

NCWC News Service

story from July 2, 1964, said churches played a major

role in “tipping the scales” in favor of passage of the Civil Rights Act by actively

supporting it from the time President John F. Kennedy spoke of plans to introduce

it in 1963 and the year plus that it was debated and voted on in Congress.

See CIVIL RIGHTS-BISHOPS, page 15