42

/ BUILDING DIALOGUE / DECEMBER 2017

B

eauty in design inter-

twines with continually

transforming market

interests. Communities, and

the building industry, refocus

regularly, incorporating new op-

portunities and challenges fac-

ing local and global populations

as well as emerging technologies

and evolving aesthetic preferenc-

es. While the quest to create beauty

in our environment remains con-

stant, we repeatedly redefine our

perception of it, along with how it’s

achieved.

For decades we debated defini-

tions of “sustainable design,” nev-

er agreeing on the nuances. Most

recently we transferred this focus

to “health.” In this refinement lies

a powerful opportunity for com-

plex beauty: architecture designed

to promote human health across

all scales, from individual through

community to global. Architecture

for life.

Growth of populations, cities and

human demands are shaping our

planet, recalibrating and redefin-

ing our relationship to it as quickly

as it transforms. There is no limit

to imaginative visions of how our

earth will look, and support life, in

decades to come. This change will

be our legacy, and it is up to us to

choose if it will be beautiful.

How do we do this, choose beauty, support life?

Human health for life.

One pathway includes de-

signing for human health, never losing sight of in-

extricable ties connecting scales. The only reason-

able solution prioritizes all of them, considering

every being impacted by a project, through direct

experience of the architecture or direct experience

of the global transformation that the architecture

drives. A project’s impact extends beyond its occu-

pants, or future generations, or people elsewhere

in the world; it falls upon every living being: each,

and all, alive today and in years to come.

Carbon dioxide offers a simple example. Most

often discussed as a greenhouse gas tied to global

warming, impacts at the individual scale gained

attention in 2014 when the Harvard TH Chan

School of Public Health, SUNY Upstate Medical

University and Syracuse University released their

rigorously conducted “COGfx” study. Their research

showed substantial declines in human cognitive

performance as carbon dioxide levels increased

within building interior spaces. No problem; we

can easily remedy this through increased outdoor

air ventilation, flushing carbon dioxide.

But the problem gains significance when we

consider that, for thousands of years, atmospher-

ic levels of carbon dioxide remained below 300

parts per million. Between 1958 – when the Nation-

al Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration first

tracked atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide in

Mauna Loa – and 2016, mean levels rose from 315

to 403 ppm. They continue to climb, exponential-

ly faster as populations grow and energy demands

increase, toward levels now quantifiably known to

impact human cognitive function. Higher-think-

ing capacity as well as productivity are threatened,

potentially this century, possibly even within de-

cades, worldwide.

This is one poignant example of many. This year

the Medical Society Consortium on Climate and

Health, representative of more than 50 percent of

U.S. medical professionals, documented regionally

specific individual health impacts resultant from

climate change, observed through direct patient

experience. Besides extreme weather events, they

highlighted infections borne by pests, tainted wa-

ter, foods and agriculture along with wildfires, air

quality and extreme temperatures. All emerged

Christy Collins,

AIA, LEED AP

BD+C

Director of

Sustainabil-

ity, Davis

Partner-

ship Ar-

chitects

ELEMENTS

Sustainable Design

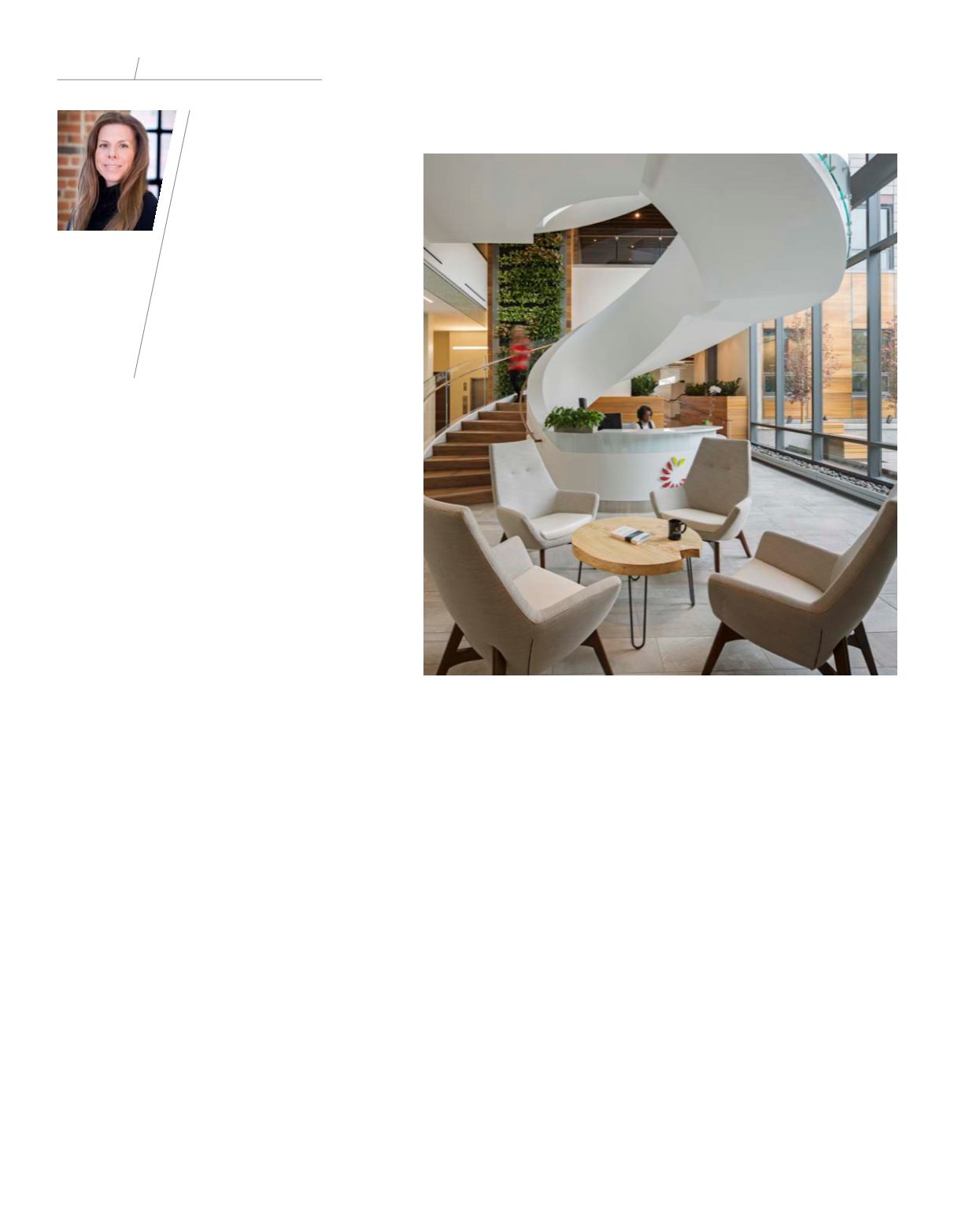

Architecture for Life: Beauty in the Built EnvironmentFrank Ooms

The interior photo captures the stair, green wall, biophilic indoor/

outdoor spatial connection and warm materials.