Page 28B—

COLORADO REAL ESTATE JOURNAL

—

September 2-September 15, 2015

T

he American

Arbitration

Association recently

revised its Construction

Industry Arbitration Rules

and Mediation Procedures.

The revised Rules, effective

July 1, send a clear message:

Arbitration should be a faster,

cheaper and more efficient

alternative to court litigation of

complex construction matters.

Parties who ignore this may feel

the force of arbitrators’ newly

enhanced sanction powers.

Parties who fail to learn the

newly revised rules could miss

important opportunities to

shape the issues, scope and

costs of the proceedings.

n

Mediation.

Mediation is

required for cases with claims of

$100,000 or more. Mediation,

by default, will happen

concurrently with arbitration.

Potential benefits of this

include reduced preparation

costs, fewer scheduling issues,

and a venue for efficiently

disposing or smaller, collateral

claims just before the hearing.

Drawbacks might include a lost

opportunity to resolve matters

early in the proceedings and a

chilled negotiating atmosphere

given the proximity to the

hearing. If the concurrent

mediation issue makes parties

uncomfortable, Rule 10

allows them to agree to other

timelines and procedures,

or to opt out of mediation

completely.

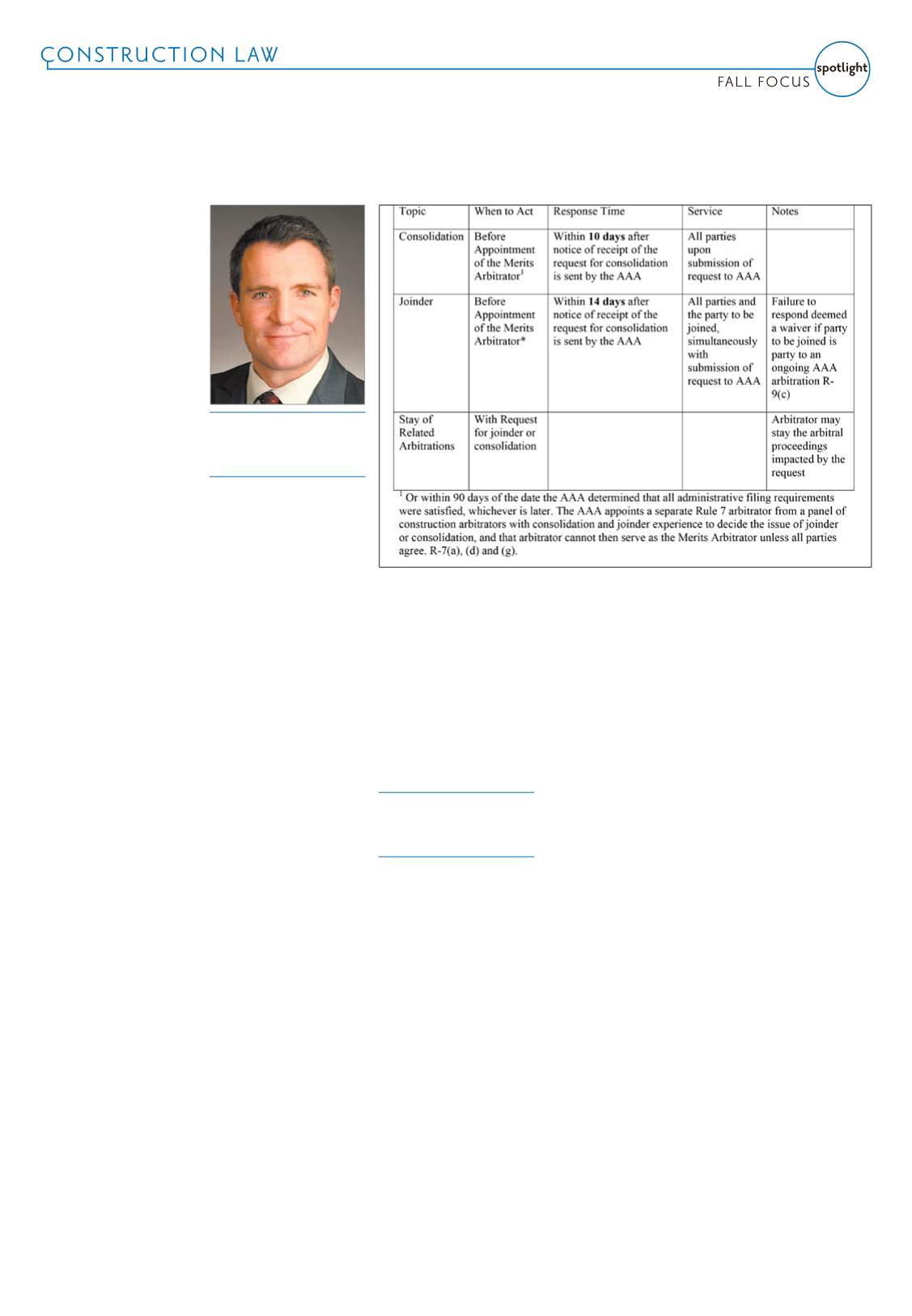

n

Consolidation and

joinder time frames and filing

requirements streamlined.

General contractors or owners

may want to act promptly

and utilize these rules to

gain control over a potential

multiparty, multitier dispute.

Also, it may make sense and

save costs to agree to allow

the Rule 7 arbitrator to act

as a merits arbitrator, or to

act as the mediator later in

the proceedings, since that

person will already have some

familiarity with the issues in the

case.

n

Preliminary hearing.

At

the discretion of the arbitrator,

and depending upon the

size and complexity of the

matter, a preliminary hearing

is to be scheduled as soon

as practicable following the

C

ontractors, owners

and banks use lien

waivers to control the

risks associated with mechanic's

liens. A mechanic's lien is a

statutory interest that someone

can assert in another person's

property to secure the payment

for improving that property.

A lien waiver abandons the

right to claim a lien, either in

whole or in part, on a particular

piece of property. A partial

lien waiver, for example, could

waive the right to lien for work

performed on a past month's

invoice. This would not waive

the right to assert a lien for

other unpaid work in the

future, or since the time the

invoice was generated. A full or

final lien waiver, on the other

hand, waives all rights to assert

a mechanic's lien for any work

performed.

Colorado's mechanic's lien

law exists to secure payment

of those who improve real

property. (Seracuse Lawler

& Partners Inc. v. Copper

Mountain, 654 P.2d 1328, 1330

[Colo. App. 1982]). Even so,

Colorado court will enforce

lien waivers if the waivers meet

minimum criteria.

First, a lien waiver must

be clear and unambiguous.

(Bishop v. Moore, 323 P.2d

897 (Colo. 1958); Ragsdale

Bros. Roofing, Inc. v. United

Bank of Denver, 744 P.2d 750

[Colo. Ct. App. 1987].) The

lien waiver must show the

clear and specific intent to

waive lien rights. (See Bishop,

supra.) If the lien waiver can

reasonably be interpreted in

more than one way the waiver

is ambiguous. (See Hecla Min.

Co. v. New Hampshire Ins. Co.,

811 P.2d 1083, 1091 [Colo.

1991; see also Bishop, supra.])

A lien waiver that is ambiguous

will be interpreted to waive

only the rights associated with

the payment actually made

in return for the waiver, but

all other lien rights remain

preserved. (Ragsdale Bros.

Roofing, Inc. v. United Bank of

Denver, 744 P.2d 750 [Colo. Ct.

App. 1987].)

Second, a lien waiver must

be supported by consideration.

(Western Fed. Sav. & Loan

Ass'n v. National Homes Corp.,

445 P.2d 892, 897-898 [Colo.

1968]; see also In re Woodcrest

Homes, Inc., 15 B.R. 886, 888

[D. Colo. 1981].) This typically

means the person or party

signing the lien waiver must

be receiving a bargained-for

benefit in return. (See Western

Fed. Sav. & Loan, supra at

897.) Some might think that

payment of a contractor's or

subcontractor's invoice will

suffice as consideration for

a lien waiver, but that is not

always the case.

For example, lien waivers

printed on the backs of checks

given to pay subcontractor

invoices may not be enforceable

if those lien waivers are not

otherwise supported by

consideration. (See generally,

In re Woodcrest Homes,

supra [held that the lien

waivers in that case were

supported by consideration].)

If a contractor already has a

contractual obligation to pay it

subcontractor, the making of

that payment is considered a

pre-existing obligation and does

not constitute consideration for

the lien waiver, except as to the

amount of the payment actually

received. (See Ragsdale Bros.

Roofing, Inc. v. United Bank

of Denver, 744 P.2d 750 [Colo.

Ct. App. 1987]; see generally

Lucht's Concrete Pumping, Inc.

v. Horner, 255 P.3d 1058, 1062

[Colo. 2011][recognizing that

performance of pre-existing

obligation does not constitute

consideration]; see also 3

Williston on Contracts § 7:36

[4th. Ed.][2015.])

If, however, the contract

with the subcontractor states

that the subcontractor must

sign lien waivers to receive

payment, then this constitutes

a reciprocal bargain (the

contractor has bargained

for the lien waiver and the

subcontractor has bargained

for the payments and the award

of the subcontract itself) and

the lien waivers are therefore

supported by consideration.

(See Western Fed. Sav. &

Loan Ass'n of Denver v. Nat'l

Homes Corp., 445 P.2d 892,

897-98 [1968][Consideration

is measured as of the time of

making the contract and need

not be of equal value to the

right given up in exchange];

see e.g., Steveco, Inc. v. C&G

Inv. Assoc., 1977 WL 200326

[Ohio case stating that lien

waiver provision in original

contract was supported by

the consideration for the

contract itself and required no

independent consideration.])

As another example, if a

lender agrees to lend further

money to complete a job that

has gone over budget due to

change order, and the lender

requires lien waivers with each

pay application as part of its

agreement to lend the extra

money, the agreement to

lend more money suffices as

consideration to enforce those

lien waivers. (See Western Fed.

Sav. & Loan, supra.)

Risks exist beyond the issues

of ambiguity and consideration.

Signing a lien waiver still can

have serious consequences

that may prevent you from

successfully asserting a lien

claim. For example, an owner

who relies on the lien waiver

of a subcontractor in making

payment to the general can

prevent the subcontractor from

successfully asserting a lien.

The legal concept behind this is

called estoppel, and it basically

binds the subcontractor to

the lien waiver to prevent

an unfair surprise to a third

party who relies upon that lien

waiver. Lenders or higher-tier

contractors also can assert

estoppel defenses based upon

a signed lien waiver from a

third party if they rely to their

detriment on that lien waiver.

(See Mountain Stone Co. v.

H.W. Hammond Co., 564 P.2d

958 [Colo. 1977].)

Another potential risk of

signing a lien waiver is that

it may contain additional

provisions, such as waivers of

other claims. Signing a claim

waiver like this could prevent

you from seeking a change

order for delays or other

impacts. The waiver form might

also include a warranty that you

have paid all of subcontractors

or suppliers in full and might

require you to indemnify the

owner if your suppliers or

subcontractors make claims. In

short, read what you are signing

and call your attorney if you

have doubts.

Finally, understand that your

lien rights belong to you. No

one can waive them on your

behalf and you cannot waiver

the lien rights of others without

their consent. (Aste v. Wilson,

59 P. 846 (Colo. Ct. App.

1900).)

Daniel C. Wennogle

Attorney, Stinson Leonard Street

LLP, Greenwood Village

Daniel C. Wennogle

Attorney, Stinson Leonard Street

LLP, Greenwood Village